“…a sharp wild brace came suddenly into the air. We drew in deep breaths of it as we walked back from dinner through the cold vestibules, unutterably aware of our identity with this country for one strange hour, before we melted indistinguishably into it again.”

– The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

1 Year

South Sudan – Kenya – Uganda – India – England – Morocco – Spain

I am stateside for the first time in a year, utterly conscious of myself, the marks Africa has written on me, and the great big different-ness that is America.

I’ve traded the violent green aerials of the Rwenzoris on the equatorial horizon for the quietly fading layers of the Blue Ridge, swapped puff adders for copperheads, packed mud and corrugated tin for brickwork and stained wood paneling, the miles and miles of battered and pot-holed red earth between Mundri and Juba for interstate highway systems blazing with a thousand thousand fires of red taillights and the flash of American dollars packed in pistons and Lexus hoods that seem like they’d nearly suffice to buy the whole of Western Equatoria.

Here, I drive a small blue hatchback (until the blessed advent of the motorcycle. It’s comin’ folks). It doesn’t have four-wheel drive, let alone a winch, and probably wouldn’t last five miles in Africa. My trusty little netbook, faithful companion in my writing career over four continents, may have finally succumbed to its slash-crack-casualties taken crossing the mountains in Western Uganda in a bouncing and jam-packed Mutatu. The borrowed computer on which I write this post on plays a “Handclapping and Footstomping” playlist on a program called Songza, which didn’t exist when I left and would likely have destroyed the internet in Africa. After fitting everything I own for a year into a green army sea bag, I come home to rediscover my library of hundreds of books, and clothes I forgot I owned. Grocery stores carry somewhere around 40,000 varieties of window cleaner, and salad dressing, and shampoo. I sign for a purchase with my finger on an iPad.

When you leave for year, everyone gets married. It’s like some kind of conspiracy of inevitable descent into domesticity. Friends have serious conversations about kitchen cabinet fixtures. They’re making the transition (as a couple) from white to wheat pasta. They buy houses. I buy another cup of coffee and sweet talk the husbands into coming rock climbing with me.

“…I came back restless. Instead of being the warm center of the world, the Middle West now seemed like the ragged edge of the universe.” (Fitzgerald)

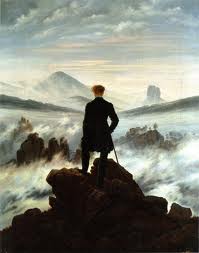

I am and always have been perpetually restless. Africa fit well with how I’m wired, and put me more in my element than anywhere else I’ve ever been. It’s a place of roaring beauty and heartbreak, wild adventure and terror, a deep sense of purpose and an unshakeable realization of how little you know, how little you control, and just how big and close and absolutely necessary is the God to whom we cling and for whose kingdom we strive. I fear that after such tangible vitality, the good old US of A could seem like Fitzgerald’s “ragged edge of the universe.” A grey pause on the waiting edge of the real, active life that lurks in the dark spaces of the map.

Yet, in a very real way, though things are inevitably different, coming back does feel like coming home, if only for a time. But home isn’t and can’t be limited here to a single house, or a single family or state, or Continent really. Home requires some work and some time on the road. Home looks like the feel of my old guitar on calloused fingertips while my brother pounds out Mumford and Sons on the faded keys of a piano in the house we grew up in. Home looks like coming into a stone-walled basement brewery and being ambushed by one bear hug after another as you realize you know and love nearly everyone in the sleepy Tennessee neighborhood. Home looks like conversations in coffee shops and front porches, aussie rappelling down cliff faces, and rediscovering old stomping grounds with old friends.

Home takes work. It takes intentionality. It’s hard to define. It grinds against the restless and forces me to try to rest (not my strong suit). “Home” is floating somewhere over the Atlantic, trapped between the grins of family and friends in Virginia and Chattanooga and the pull of the was and the will be of the grit of Africa and South Asia.

This is a present and coming season of in-betweens, but it must not be a season of aimlessness. Even if I’m not in darkest Africa or the maze-like streets of India, and even when I desperately want to be, there’s plenty to be done and learned here and now.

Then of course there’s my growing to-do list for the months in the U.S. to work towards the next overseas assignment and to stave off my seemingly insatiable desire for new challenges and new adventures. Cross country motorcycle trips are in the works, my first triathlon, reading anything and everything to become an expert on India and human trafficking.

As I lay out the first draft of this blog post, I’m sitting on a mountain ridge and watching the show as another day and another chapter of the story turns over on its axis and gives way to the stars. The sun is peeling back layers of light and scattering a dusting of American gold from the stratosphere and over the rolling hills. The humid Georgia heat smells like rotting logs and nostalgia and the wind whips in bursts that rattle the grass and the branches like castanets. I’m on the edge of so many things.

“The city seen from the Queensboro Bridge is always the city seen for the first time, in its first wild promise of all the mystery and the beauty in the world…. Anything can happen now that we’ve slid over this bridge,” I thought; “anything at all…” (Fitzgerald)

P.S. – I’m planning on keeping on writing in the U.S., trying to chronicle the next steps of transition from Africa to India with continuity. But now comes the question of what to name my blog. “Shaughnessy in South Sudan” only works when I’m in South Sudan. It needs to be something more general that can work across hemispheres and countries. Ideas anyone?